Socialist China’s Successes

I felt that we had neglected China’s successful application of socialism compared to how much we covered the implementations in the USSR and Albania. That is why we shall make this post. (We will borrow heavily from our almost-done book.)

The CPC liberated China from the KMT’s government in 1949, founding the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

China’s economy expanded rapidly in the 1950s, and it guaranteed education, housing, employment, healthcare, etc. The USSR provided economic and technical aid, allowing China’s first five-year-plan to be a marvelous success as steel production quadrupled, coal production doubled, industrial output doubled, and more.

On top of these, China’s system was democratic for the workers and peasants. The people exercised dictatorship over the enemy classes, and the workers had a say in economic planning, wages, and more. Because the party and state had to listen to the masses, the masses held real power, unlike under the KMT. In “Industrial Management in China”, Ma Wen-kuei wrote:

Democratic centralism is fundamental in the administration both of our state and of our socialist state-owned industrial enterprises. Comrade Liu Shao-chi has pointed out: “The system adopted in managing our enterprises is a system which combines a high degree of centralization with a high degree of democracy. All enterprises must abide by the unified leadership and planning of the [Communist] Party and the state, and, by observing strict labor discipline, ensure unity of will and action among the masses. At the same time, they should bring into full play the initiative and creativeness of the workers, develop the supervisory role of the masses, and get them to take part in the management of their enterprises.”

All management in our enterprises must conform to the spirit of democratic centralism. This fully suits the socialist nature of our industrial enterprises and the objective demands of modern industrial production. Both the nature of ownership by the whole people of the enterprises and the highly socialized nature of modern industrial production call for a highly centralized and unified leadership. Failing this, socialized production cannot be carried out in a normal way, nor can the principles, policies and plans of the Communist Party and the state be implemented thoroughly. But the centralized leadership of socialist industrial enterprises, in which staff and workers are also masters and enjoy the right to participate in management, is fundamentally different from the arbitrary dictatorship existing in capitalist enterprises. It should and can be combined with extensive democracy. Our system of democratic centralism is centralism based on democracy, and democracy under centralized guidance.

[Source]

In Rethinking Socialism, the authors explain:

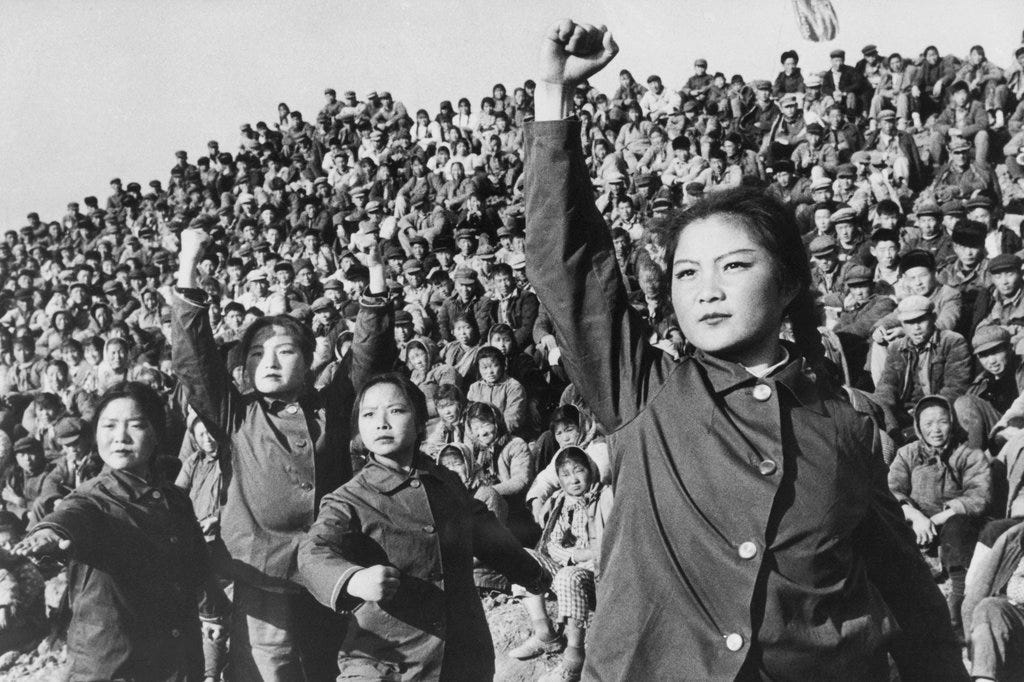

Whether the cadres had followed the mass line or not could be tested in mass movements. Mass movements provided an open forum where the masses could voice their opinions and express their discontent, criticizing party members for any wrongdoing and abuses of power. Participation in mass movements raised the consciousness of workers and peasants and generated new ideology. Major policies implemented during the socialist transition were accompanied by mass movements where new ideas were propagated and important issues debated. If such policies indeed promoted the interests of the masses, the masses would eventually adopt them. Mass movements in the past provided the opportunity for the government to seek the validation of its policies by the masses. Policies so validated had better chances to succeed. Mass movements also aroused the enthusiasm of the masses and empowered those who were in favor of the policy.

[Source]

It is true that many opponents were suppressed under Mao, but these were reactionary opponents and dissidents that the people helped in suppressing and attacking. Mao opposed the liberal use of execution against opponents, and he frequently let people go after they served prison sentences. The masses supported suppressing counter-revolutionaries, and free expression flourished as long as it remained within the context of advancing socialism and defending the existing state (even if it meant criticizing the state to help improve it).

Mao, in contrast to what bourgeois media says, supported free speech in the Hundred Flowers Campaign of 1956, which was based on him saying, “Let a hundred flowers bloom, and a hundred schools of thought contend.” He wanted as many suggestions and criticisms as possible, to help perfect the socialist system. This led to anti-communists abusing this by spreading misinformation and advocating for the overthrow of the proletariat’s dictatorship. Within the Communist Party, capitalist-roaders like Deng Xiaoping condemned the Hundred Flowers Campaign for this, so the Anti-Rightist Campaign came about, led by Deng. While Mao recognized that the people needed to condemn reactionary ideology, he did not believe that many people were actually reactionary; Deng, in contrast, allowed hundreds of thousands to be persecuted despite not necessarily being rightists. This was one of the first examples of China’s line struggle that would continue all the way until Mao died and even a little after that. Silage Choppers and Snake Spirits clarifies this:

As part of an effort to shake things up before that kind of thinking got solidified into party culture, in 1956 Mao launched a movement called, “Let a Hundred Flowers Bloom and a Hundred Schools of Thought Contend.” The idea was to encourage critical thinking and new ideas, in arts and culture (flowers) and science and technology (schools of thought).

The Hundred Flowers Campaign, as it came to be known, initiated a flurry of papers and articles written about what was happening in China and where it should be going as a country. Among the writers were people, mostly intellectuals, who launched attacks on the Party and called for the Party to step down. Their call was for a two-party system, and since the Communist Party had been in power already for six years, it was time for them to move aside and let other people take power.

In what would become Mao’s preferred method in dealing with people who were attacking the socialist principles of the Party, his instructions were to let them say and do what they wanted so that the people themselves could understand what they were about, by seeing and experiencing firsthand their intentions and motivations. After about twenty days, those calling for a two-party system had become increasingly high pitched in their rhetoric. And the people in general were pretty pissed off. So through the Party paper, the Party countered, laying bare the different issues involved with socialist development and the dictatorship of the proletariat.

It would later be articulated at a meeting at Lushan (Lu Mountain in Jiangxi Province) in 1959, but at the crux was that two ideological lines emerging since Liberation were becoming more apparent. Put simply, one was socialist and one was capitalist, and the Party was split from the very top, with Mao and Zhou Enlai on one side, and Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping on the other. Essentially, all of the complex and heated movements that followed, including the Hundred Flowers Campaign, straight through to the Cultural Revolution, were an expression of this ideological struggle among the Party’s top leadership.

The Hundred Flowers Campaign ended with Liu and Deng criticizing Mao for unleashing the bourgeoisie and allowing them to attack the Party. And because there had been an attack on the Party, the Anti-Rightist Movement was launched in 1957 in order to seek out the people behind it. Deng Xiaoping was given the responsibility of running it. …

In a short time, however, the Anti-Rightist Movement turned ugly. At its start, Mao estimated that there were maybe 400 Rightists in Beijing and 4,000 in the entire country. Within three months under Deng’s leadership, however, 300,000 people had been targeted and accused in a bona fide witch-hunt.

[Source]

In 1960, after China’s proletarian leaders refused to submit to his demands to put China’s military under Soviet control, Khrushchev removed the technicians and scientists necessary for economic development from China, and this weakened China’s industrialization efforts of the Great Leap Forward for a time. In the same year, the CPC called Khrushchev a revisionist openly, leading to the inevitable Sino-Soviet split, a divide between the revisionist, imperialist USSR and revolutionary, socialist China. Albania took China’s side while, as we said earlier, the other People’s Democracies submitted to Soviet imperialism and became comprador-bourgeois states. China was the last socialist state in Asia, and Albania was the last one in Europe.

The USSR also demanded China’s repayment of its debt, and this meant that China would either become dependent on the USSR (making it a semi-colony of the imperialists like it was before the revolution) or would have to pay up extremely fast. China took the second option, completely being debt-free in 1964. The debt payment, problems with weather that damaged crops, the rampant overreporting that went on during the movement, and more, the Great Leap Forward had failings. Nonetheless, it was not “the worst famine in the universe” as reactionaries tend to say. “Leap Forward” defends the movement while recognizing its immense problems (our bolding):

The challenges they had to overcome were intimidating. China had no coal or petroleum, and they were told by the phony-communists and capitalists: that will be the death of your economy. But in the Great Leap, they uncovered unknown resources of coal and petroleum by mobilizing the masses on a huge scale to find it. They developed a radical critique of Soviet economics which was foundational to the Marxist understanding of political economy, and that was critical to the success of developing all three components of Marxism which made MLM [Marxism-Leninism-Maoism] possible as the third and highest stage. Mao wanted discover ways to decentralize industry and find ways to proletarianize the peasantry. Programs to spread technical knowledge, and working class experience to the peasantry were put into place. Putting these ideas into motion, Chairman Mao Zedong was following through with the powerful words of The Communist Manifesto: “Combination of agriculture with manufacturing industries; gradual abolition of the distinction between town and country, by a more equitable distribution of the population over the country.” And so they began to do this, with the workers and masses in command. …

Outside Daqing with oil, elsewhere with the Great Leap Forward beginning, the Communist revolutionaries built small operations in the countryside—to serve agriculture. Small shops that could make blades for plows, for example. Small machine shops that could repair pumps also came about; and of course they began to develop local steel. Great amounts would be required to make the project succeed, and [they] did [not] have the resources or expertise for large modern blast furnaces. Some called Mao “insane” for developing these new techniques, but how did they expect the Chinese to develop steel? No prayer would make it fall from the sky. …

During the Great Leap Forward, there was a huge, parallel development in agriculture: the People’s Communes. The Chinese people developed a collective form that was basically at the county level. That meant that the peasants could pool resources on a much larger scale—develop canals and machine shops and side industries. All of this was impossible at the small-collective or family farm level; only during the Great Leap Forward did this begin to happen on a massive scale. Afterwards, they had a basis for commune machine shops, to send kids for technical training, etc.

However, did the furnaces lead to bad crops? No, as we know, in feudal times agriculture went by human-pulled and animal-pulled plows. And these furnaces did develop usable plows. There was no mechanized agriculture yet (except in a few advanced areas)—the whole point was/is to develop agriculture and industry. The furnaces did not “destroy” mechanized agriculture; the process laid the basis for Chinese peasants to be able to deal with machinery and technical things. They developed collective forms (at the People’s Commune levels) to develop the furnaces—and those forms were later used to set up machinery repair places etc.

The socialist revolution made it possible to deal with famine in new ways. There was rationing and food sharing. Areas that had good harvests sent food to areas with bad harvests. The burden and impact of the bad harvests was softened by all the new forms that socialist made. It was new and breathtaking, and saved many lives. The Great Leap Forward had its shortcomings, yes, but the way they handled those shortcomings showed the strength and superiority of socialism over capitalism.

[Source]

The Great Leap Forward’s death toll estimate has ranged from as low as two million deaths to as high as 60 million. Scholars have not agreed on the actual death toll of this program, but many more are starting to find lower death tolls as more information is uncovered and the old anti-communist propaganda machine weakens. In “Sun Jingxian and the Myth of Mass Genocide. The Last Word?”, the author states:

New research in China seems to have finally demolished the myth that tens of millions died due to the actions of Mao in the Great Leap Forward. Rather it seems that the famine of 1959–1961 was the last of a series of famines that China had endured throughout its history. The actual death toll figures for this famine were comparable to previous famines and had the same underlying cause-the poverty of a country that had been kept in a state of economic backwardness by imperialism. …

The article presents evidence for a figure of 3.66 million deaths due to famine. It is 12% of the 30 million figure favored by Judith Banister and other American demographers in the 1980s. It is 8% of the 45 million figure favored by Frank Dikotter. It is equivalent to about 0.5% of the country’s population dying over a three year period. If true, it is still a tragic death toll, even if it is lower than previously believed estimates. However, we must acknowledge that a very poor country, as China still was in the 1950s and early 1960s, was very susceptible to famine. As western demographers accept a Chinese famine in 1928–31 had left 3 million dead, a 1936 famine in west China had claimed 5 million lives:

We must also acknowledge that the famine of 1959–61 was thankfully the last famine China was to suffer. Finally, we must acknowledge there is no certainty about the figure of 3.66 million. Rather Sun’s article shows how certainty about the figures we have from this era can never be properly achieved. We do not and probably will never know if the true figure was less or more than 3.66 million.

Sun’s figure is the total figure for all deaths in excess of the total deaths in the ‘good year’ of 1957 when the death rate reached a historic low point in China. It does not necessarily mean 3.66 million starved to death, it includes those dying prematurely due to the effect of poorer nutrition on already fragile health, etc. Even without famine, death tolls could have fluctuated above the 1957 figure in some years anyway.

What Sun Jingxian’s article does show is that the real figure can be nowhere near 11.5 million or 30 million or any of the other previously believed figures.

[Source]

The higher death tolls commonly attributed to the Great Leap Forward—and by extension blamed on China, Mao, and socialism/communism in general—come from faulty methods of measurement. In “Did Mao Really Kill Millions in the Great Leap Forward?”, Joseph Ball explains:

A variety of Chinese figures are quoted to back up this thesis that a massive famine occurred. Statistics that purport to show that Mao was to blame for it are also quoted. They include figures supposedly giving a provincial break-down of the increased death rates in the Great Leap Forward, figures showing a massive decrease in grain production during the Great Leap Forward and also figures that apparently showed that bad weather was not to blame for the famine. These figures were all released in the early 1980s at the time of Deng’s “reforms.”

But how trustworthy are any of these figures? As we have seen they were released during the early 1980s at a time of acute criticism of the Great Leap Forward and the People’s Communes. China under Deng was a dictatorship that tried to rigorously control the flow of information to its people. It would be reasonable to assume that a government that continually interfered in the reporting of public affairs by the media would also interfere in the production of statistics when it suited them. …

Even if it was granted that such shortfalls did occur they do not necessarily indicate massive numbers of deaths. Birth rate figures released by the Deng Xiaoping regime show massive decreases in fertility during the Great Leap Forward. It is possible to hypothesize that there was a very large shortfall in births without this necessarily indicating that millions died as well. Of course, there had to be some reason why fertility dropped off so rapidly, if this is indeed what did happen. Clearly hunger would have played a large part in this. People would have postponed having children because of worries about having another mouth to feed until food availability improved. Clearly, if people were having such concerns this would have indicated an increase in malnutrition which would have led to some increase in child mortality. However, this in no way proves that the “worst famine in world history” occurred under Mao. The Dutch famine of 1944-1945 led to a fertility decline of 50%. The Bangladesh famine of 1974-1975 also led to a near 50% decrease in the birth rate. This is similar to figures released in the Deng Xiaoping era for the decline in fertility in the Great Leap Forward. Although both the Bangladesh and the Dutch famines were deeply tragic they did not give rise to the kind of wild mortality figures bandied about in reference to the Great Leap Forward, as was noted above. In Bangladesh tens of thousands died, not tens of millions. …

If India’s rate of improvement in life expectancy had been as great as China’s after 1949, then millions of deaths could have been prevented. Even Mao’s critics acknowledge this. Perhaps this means that we should accuse Nehru and those who came after him of being “worse than Hitler” for adopting non-Maoist policies that “led to the deaths of millions.” Or perhaps this would be a childish and fatuous way of assessing India’s post-independence history. As foolish as the charges that have been leveled against Mao for the last 25 years, maybe.

[Source]

[Source]

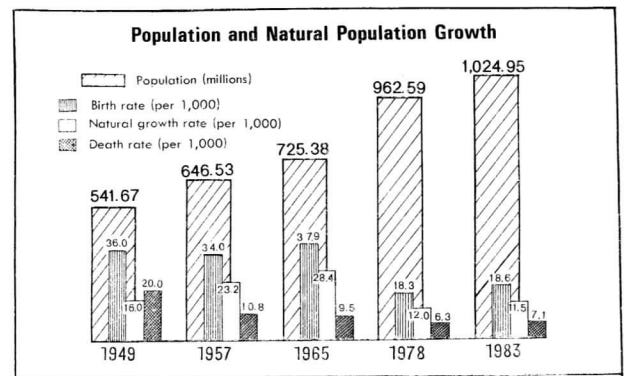

Remember that China used to have famines on a regular basis before the revolution; at least 1828 famines were recorded between 108 BC and 1911 AD, meaning that for more than 90% of that time, China experienced famine. China also had multiple famines under the KMT, in 1911–43. After the famine in the Great Leap Forward, China successfully secured food for its population. This, combined with improved healthcare, education, universal employment, increased housing, etc. that came from the socialist system, improved China’s life expectancy and quality of life. The People’s Communes in China’s agriculture allowed mechanization on a large scale, and this helped secure food; economic planning and the policy of lowering basic needs’ prices or providing them for free also contributed to this marvel.

China had many issues to resolve with neighboring countries. Specifically, it had to fight Indian expansionism, and it supported anti-revisionist Marxist-Leninist uprisings in India and Burma. Both India and Burma had the support of the revisionist USSR, but China took a socialist stance against these reactionary regimes. To understand the issue between India and China, we must go back to the late 1950s. After India’s status as a direct British colony ended in 1947, the Indian bourgeoisie sought to take various regions north of their country, particularly those near China. China and India were initially decent allies, both being part of the “Bandung Conference” in 1955, but after the revisionist USSR allied with India, relations with China deteriorated. In Part 1 of The Himalayan Adventure, in “The Indian Rulers’ Expansionist Policy”, Suniti Kumar Ghosh describes this:

After Britain’s direct rule of India ended, the Indian rulers directed their attention to India’s northern neighbors: the Himalayan kingdoms of Kashmir, Nepal, Bhutan, Sikkim and Tibet. Even before the end of direct colonial rule the Nehrus wanted to annex Kashmir. Jammu and Kashmir (J and K) was then a native state under British paramountcy. (On the transfer of power in ‘British India’ J and K was free to accede to India or not.) On 14 June 1947, V.K. Krishna Menon, Nehru’s confidant, made a fervent appeal to viceroy Mountbatten to ensure the state’s accession to India. On 17 June, on the eve of Mountbatten’s visit to J and K, Nehru himself wrote a long note to the viceroy pleading for Kashmir’s joining India. When the maharaja of J and K acceded to India in October 1947, the instrument of accession had a proviso that the accession would be final only after law and order was restored and the people of J and K freely decided in favor of it. On behalf of the Indian government Nehru gave repeated pledges to the people of J and K and to the United Nations Organization that this issue of accession would be decided finally “according to the universally accepted norm of plebiscite or referendum”. But Nehru indulged in double-talk of which he was a consummate master. The Indian ruling classes would not allow the people of J and K to decide their own fate through a fair plebiscite. Today their political managers are more brazen-faced than before and claim that J and K is an integral part of India. So J and K lies torn into two parts—about one third under the occupation of Pakistan and the rest under the virtual military occupation of India—and ravaged by hostile forces.

On 7 November 1950 Patel, India’s home minister, wrote to India’s prime minister, Nehru: “The undefined state of the frontier [in the north and northeast] and the existence on our side of a population with its affinities to Tibetans or Chinese have all the elements of potential trouble between China and ourselves. Our northern or north-eastern approaches consist of Nepal, Bhutan, Sikkim, the Darjeeling and tribal areas in Assam…. The people inhabiting these portions have no established loyalty or devotion to India.” He suggested that “The political and administrative steps which we should take to strengthen our northern and north-eastern frontiers” were to “include the whole of the border, i.e., Nepal, Bhutan, Sikkim, Darjeeling and the tribal territory in Assam.”…

Nehru considered Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) to be “really part of India” and wanted her to be included within an Indian federation. Nepal, too, according to Nehru, was “certainly a part of India” and, as Chester Bowles, Nehru’s friend and US ambassador to India for two terms, said: “So India has done on a small scale in Nepal what we have done on a far broader scale on two continents.”

[Source]

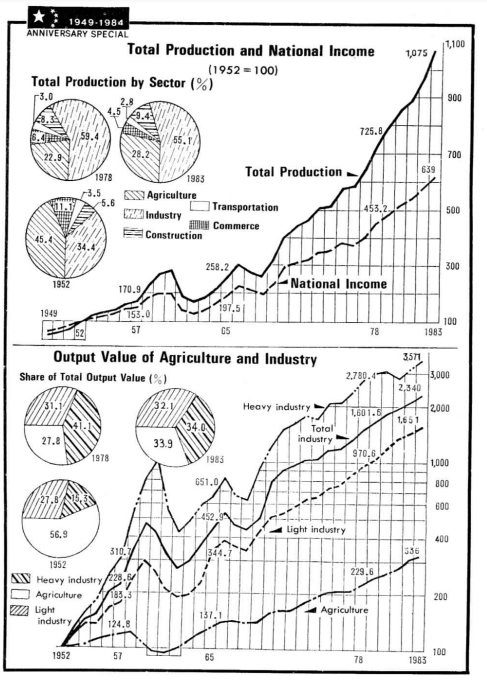

As the text says, India was interested in many areas near China. It annexed Jammu and Kashmir shortly after its independence. Other areas were either subject to its domination or annexed later. Tibet was the exception, for it was technically part of China; nobody recognized the “independent” government of Tibet, but the US and India wanted to use that illegitimate body as a puppet to attack China with. After the Communists in China took power, the US sought to recognize Tibet as an independent nation; the reason the US did not do this earlier was that the KMT, a US ally, previously controlled China and claimed Tibet. After China sent troops to Tibet in 1959 to stop a revolt from slave owners and landlords, the revisionist Soviets backed India, the primary supporter of the Tibetan reactionaries. This betrayal coincided with the Soviet removal of technicians, specialists, etc. sent in 1950 to assist in China’s economic development; after China refused to submit to the developing Soviet capitalist-imperialism, the Soviets worked with the US and tried to weaken China. With the imperial core united against China, sabotage in Xinjiang from both the US and the USSR, and attacks from India, China had no choice but to respond with force. China fought a war with India in 1962 to maintain its sovereignty against imperialist aggression. China won the war, but it only took control of small regions of India, and it left most of its captured regions to India. India and China would continue to be rivals, with the imperialists—mainly the Soviet ones, but also American to a degree—backing India to try to weaken socialist China and its influence on communist parties in Asia and worldwide. Because China was an anti-revisionist and socialist state, it experienced many benefits that the revisionist states experienced only in part. China had genuine workers’ democracy while the revisionist states’ workers felt the tyranny of the comprador bourgeoisie. As explained before, China’s economy exploded in the 1950s; it experienced downturns in the early-1960s in the Great Leap Forward and the late-1960s in the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (which will be explained later), but its growth in the mid-1960s and the 1970s (during the Cultural Revolution, that is) was so great that it negated the downturns [Source]! China greatly raised its literacy rate, life expectancy, and quality of life. It was able to begin rapid industrial development, a massive literacy and education campaign, family planning initiatives, cultural advancement, womens’ liberation, and more. It was the most advanced society with the greatest levels of democracy and freedom as long as Mao was alive. The people were in control of their workplaces and their own lives, in contrast to the dictatorships of capitalist society which are ruled by parasitic capitalists that contribute nothing to our people. It is no wonder anti-communists slander Mao’s China so much. In a footnote of Is China an Imperialist Country?, the author remarked:

In particular, China’s socialist economy expanded at a very rapid pace during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (often dated from 1966 through 1976), averaging more than 10% per year! See: Mobo Gao, “Debating the Cultural Revolution: Do We Only Know What We Believe?”, Critical Asian Studies, vol. 34 (2002), pp. 424–425; and Maurice Meisner, The Deng Xiaoping Era: 1978–1994, p. 189. Even the capitalist-roaders themselves had to admit that, except for brief declines during the Great Leap Forward and the first 3 years of the GPCR, the growth of both industrial and agricultural production during the rest of the Maoist socialist period (1969–1976) was very fast. See the charts on the second page of the article “China’s Industry on the Upswing”, Beijing Review, Vol. 27, #35 (Aug. 27, 1984)… The later claim of the capitalist-roaders that the Cultural Revolution was a “disaster” for the economy was an outright lie. Even the brief production declines of the first three years of the GPCR were very rapidly made up for beginning in 1969, and the overall trend line from before the decline and after it was as if the short decline had not even occurred!

[Source]

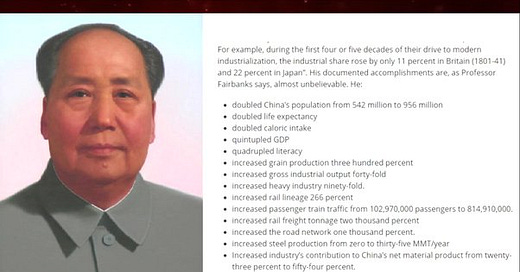

In “Mao Reconsidered”, it details the successes of the socialist era:

When Mao stepped onto the world stage in 1945, Russia had taken Mongolia and a piece of Xinjiang, Japan occupied three northern provinces, Britain had taken Hong Kong, Portugal Macau, France pieces of Shanghai, Germany Tsingtao, the U.S. shared their immunities and the nation was convulsed by civil war. China was agrarian, backward, feudalistic, ignorant and violent. Of its four hundred million people, fifty million were drug addicts, eighty percent could neither read nor write and their life expectancy was thirty-five years. The Japanese had killed twenty million and General Chiang Kai-Shek complained that, of every thousand youths he recruited, barely a hundred survived the march to their training base. Women’s feet were bound, peasants paid seventy percent of their produce in rent, desperate mothers sold their children in exchange for food and poor people sold themselves, preferring slavery to starvation. U.S. Ambassador John Leighton Stuart reported that, during his second year there, ten million people starved to death in three provinces.

When he stepped down in 1974 the invaders, bandits and warlords were gone, the population had doubled, literacy was 84 percent, wealth disparity had disappeared, electricity reached poor areas, infrastructure was restored, the economy had grown 500 percent, drug addiction was a memory, women were liberated, girls were educated, crime was rare, everyone had food and shelter, life expectancy was sixty-seven and, by several key social and demographic indicators, China compared favorably with middle income countries whose per capita GDP was five times greater.

Despite a brutal U.S. blockade on food, finance and technology, and without incurring debt, Mao grew China’s economy by an average of 7.3 percent annually, compared to America’s postwar boom years’ 3.7 percent. When he died, China was manufacturing jet planes, heavy tractors, ocean-going ships, nuclear weapons and long-range ballistic missiles. As economist Y. Y. Kueh observed: “This sharp rise in industry’s share of China’s national income is a rare historical phenomenon. For example, during the first four or five decades of their drive to modern industrialization, the industrial share rose by only 11 percent in Britain (1801-41) and 22 percent in Japan”. His documented accomplishments are, as Professor Fairbanks says, almost unbelievable. He:

doubled China’s population from 542 million to 956 million

doubled life expectancy

doubled caloric intake

quintupled GDP

quadrupled literacy

increased grain production three hundred percent

increased gross industrial output forty-fold

increased heavy industry ninety-fold.

increased rail lineage 266 percent

increased passenger train traffic from 102,970,000 passengers to 814,910,000.

increased rail freight tonnage two thousand percent

increased the road network one thousand percent.

increased steel production from zero to thirty-five MMT/year

Increased industry’s contribution to China’s net material product from twenty-three percent to fifty-four percent.

But, from Mao’s point of view, that was a sideshow. By the time he retired, he had reunited, reimagined, reformed and revitalized the largest, oldest civilization on earth, modernized it after a century of failed modernizations and ended thousands of years of famines.

[Source]

China’s Cultural Revolution was a major mass movement in 1966–76 that attempted to defend China’s proletarian dictatorship from the revisionist overthrow that occurred in the USSR and most People’s Democracies. The Chinese masses, with Chairman Mao’s guidance, attacked reactionary culture and promoted socialist and communist culture. They also removed revisionists from power and put proletarian leaders in place.

There were mistakes made in China’s socialist construction, so the Chinese masses tried to eliminate such errors. In Battle for China’s Past: Mao and the Cultural Revolution, it says:

Mao’s political experiment, the Cultural Revolution, like all other social revolutions before it, claimed many victims. It did however, again like other social revolutions, have some positive outcomes. It encouraged grassroots participation in management and it also inspired the idea of popular democracy. … The Chinese were not the brainless masses manipulated by a ruthless dictator so often portrayed in the Western media. They must be seen as agents of history and subjects of their own lives like any other people. …

Certainly there was violence, cruelty and destruction, but how should we interpret what happened during that period? … [T]here was no planned policy for violence can be seen in the sequence of events in those years. Recognizing the terrible consequences of the “Red Terror” in 1966—when in Beijing homes were raided, people judged to be class enemies were beaten up, and detention centers were set up—and determined to stop further terror of this kind, the central committee of the CCP approved a decree drafted by the CCP of the Beijing Municipality and issued it to the whole of China on 20 November 1966. … [T]he official policy was clear: yao wendou bu yao wudou (engage in the struggle with words but not with physical attack). … Neither the so-called 1967 January Storm (yiyue fengbao) that originated in Shanghai and encouraged the Rebels to take over power from the CCP apparatus, nor the suppression of the so-called 1967 February Anti-Cultural Revolution Current (eyue niliu) were meant to include physical fighting and certainly not physical elimination, though both did lead to violence of various kinds.

Much of the violence, brutality and destruction that happened during the ten-year period [of the Cultural Revolution] was indeed intended, such as the persecution of people with a bad class background at the beginning, and later action against the Rebels, but the actions did not stem from a single locus of power. To use “Storm Troopers” in reference to the Red Guards, for instance, is conveniently misleading. There was no such singular entity as the ‘Red Guards’ or the ‘Red Guard’. First, we must differentiate between university students and school students. It was the latter who invented the term ‘Red Guards’ and who engaged in acts of senseless violence in 1966. We should also note the difference between schoolchildren in Beijing, where many high-ranking CCP officials and army officers were located, and those in other places such as Shanghai, the home town of three of the so-called “Gang of Four” radicals. It was not in Shanghai, the supposed birthplace of the Cultural Revolution radicals, but in Beijing that schoolchildren beat up their teachers most violently. It was also in Beijing (in 1966) that the children of high-ranking CCP members and army officials formed the notorious Lian dong (Coordinated Action) and carried out the socalled ‘Red Terror’ in an effort to defend their parents. What they were doing was exactly the opposite of what Mao wanted, to ‘bombard the capitalist-roaders inside the Party’, that is, parents of the Lian dong Red Guards. Lian dong activists behaved like those of the Storm Troopers, but these were not Mao’s Storm Troopers. Mao supported those Rebels who criticized CCP officials including the parents of the Lian dong Red Guards. These facts can easily be confirmed by documentary evidence; yet the post-Mao Chinese political and elite intelligentsia either pretend not to see them or choose to ignore them. …

If anything the CCP under the leadership of Mao, and chiefly managed by Zhou Enlai, tried hard to control violence. Eventually the army had to be brought in to maintain order. By 1969, a little more than two years after the start of the Cultural Revolution the political situation was brought under control and China’s economic growth was back on track.

[Source]

Such mistakes are simply inevitable in socialism. We can try our best to prevent them, and we can learn from the mistakes of China’s cultural revolution, but there will always be innocents who die in class struggle, sadly; this is not particular to anti-capitalist struggle, as it has occurred in all social revolutions. In the Peking Review issue published on January 27, 1967, in an article titled, “Proletarian Revolutionaries, Form a Great Alliance to Seize Power from Those in Authority Who are Taking the Capitalist Road!” the authors declare:

In socialist society and under the dictatorship of the proletariat, hundreds of millions of revolutionary people have formed a mighty revolutionary force, with the great alliance of the proletarian revolutionary rebels as the core, to seize power from below, from the handful of people within the Party who are in authority and taking the capitalist road and from those diehards who persistently cling to the bourgeois reactionary line. This is an important development by Chairman Mao of the Marxist-Leninist theory of proletarian revolution and the dictatorship of the proletariat.

The basic question of revolution is political power. With the victory of the People’s Democratic revolution of our country, the proletariat seized power on a nationwide scale. But the overthrown class enemies remain and they are not reconciled to their defeat. … The struggle for the seizure of power has continued vigorously all the time between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. … Only by carrying out a great mass movement like this, a mass struggle to seize power in an all-round way, is it possible thoroughly to resolve the problem of the seizure of power by the proletariat, thoroughly to resolve the problem of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Power of every sort controlled by the representatives of the bourgeoisie must be seized! This is the great truth of Marxism-Leninism, of Mao Tse-tung’s thought, which the revolutionary masses have grasped through arduous struggles over the last few months. …

Reversals and twists and turns over the past several months and the repeated hurricanes of stormy class struggle gave the masses of revolutionary rebels profound lessons. They are seeing ever more clearly that the reason why the revolution suffered setbacks is due precisely to the fact that they did not seize in their own hands the seals of power. … Those who have power have everything; those who are without power have nothing. … The proletarian revolutionary masses must take firmly into their own hands the destiny of the dictatorship of the proletariat, the destiny of the great proletarian cultural revolution and the destiny of the socialist economy! They have rightly said: ‘The proletarian revolutionaries, the real revolutionary Left, have their eye on seizing power, think of seizing power and act to seize power!’ …To carry out the struggle for the seizure of power, the proletarian revolutionary rebels must effect a great alliance. In the absence of a great alliance, the seizure of power from those in authority who are taking the capitalist road remains empty talk. In the Communist Manifesto more than a hundred years ago, Marx and Engels were the first to raise the militant slogan “Workers of all countries, unite!”, sounding the drums for the proletariat’s first seizure of power which reduced the bourgeoisie of the old world to fear and trembling.

[Source]

The movement did not destroy the economy. In Battle for China’s Past, Mobo Gao states:

In the area of industrial development, Mao took a strongly socialist view, concerning himself with eradicating the usual divide between the rural and urban. Under his leadership a strategy was developed and implemented to trial a decentralized non-Soviet form of industry programme. It was proposed that the rural population could become industrialized without a need to build cities or urban ghettos, a strategy initiated during the Great Leap Forward, shelved because of the famine disaster, but picked up again during the Cultural Revolution. As Wong (2003: 203) shows, by the end of the decade of the Cultural Revolution in 1979, there were nearly 800,000 industrial enterprises scattered in villages and small towns, plus almost 90,000 small hydroelectric stations. These enterprises employed nearly 25 million workers and produced an estimated 15 percent of the national industrial output. This development provided the critical preconditions for the rapid growth of township and village enterprises in the post-Mao reform period. …

… [N]ew socioeconomic policies were gradually introduced and these had a positive impact on a large number of people; these policies were intentionally designed. These included the creation of a cheap and fairly effective healthcare system, the expansion of elementary education in rural China, and affirmative-action policies that promoted gender equality. Having grown up in rural China, I witnessed the important benefits that these policies had for the rural people. …The “positives” should also include developments in China’s military defense, industry and agriculture. … True, China’s economy was disrupted in 1967 and 1968, but throughout the rest of the late 1960s and through all of the 1970s China’s economy showed consistent growth. …It is also worth pointing out that the development of she dui qiye (commune and production brigade enterprises) during the Cultural Revolution were the forerunners of the xiangzhen qiye (township and village enterprises) developed in post-Mao China.

[Source]

Sadly, revisionism was able to develop even in the last socialist states that existed in the 20th century. Even though China remained on the socialist path for quite some time, Marxism-Leninism was eventually overthrown. After Mao Tse-Tung died, various Marxist-Leninists around China were arrested, and Deng Xiaoping and his allies reversed socialist transition and made China capitalist in 1978. This is why modern China is capitalist. The book From Victory to Defeat by Pao-yu Ching explains what happened after China’s privatization campaigns:

Deng’s Reform consisted of two interrelated components: capitalist reform in China and opening up China’s economy to link it with the international capitalist system. Within a short amount of time, Deng and his followers began to dismantle the socialist economic and social system built during 1956-1976 by fundamentally changing the relations of production, as well as the superstructure, from socialist to capitalist. The Reformers understood that the principal opponents of their Reform would be the working people (workers and peasants) so their class strategy was to create disunity among the workers to weaken their power and to break up the close alliance between workers and peasants. During the socialist construction, the state and collective ownership of the means of production was fundamental to the socialist class strategy: the unity of workers and their close alliance with peasants. To be successful the capitalist Reformers had to attack this economic base. However, since the socialist superstructure supported the socialist economic base, the capitalist Reformers had also to fundamentally change the superstructure from socialist to capitalist. …

Dissolving the communes was a calculated and necessary move for the Reformers. Without collective ownership in the countryside workers could no longer form an alliance with the peasants. The Chinese Communist Party (representing workers) had formed a close alliance with the peasants when fighting the Revolutionary and Civil Wars by promising them land reform. Peasants sacrificed their lives and their loved ones when they joined the Red Army to fight the guerrilla war. Without the peasants the Chinese Communist Party could not have won the revolution. After Liberation, the CCP strengthened the worker-peasant alliance by collectivizing agriculture and by carrying out policies that mutually benefited workers and peasants. The strong alliance between workers and peasants was key to socialist construction. When the capitalist Reformers broke the worker-peasant alliance by de-collectivizing agriculture, they weakened both the worker and peasant resistance against capitalist projects they enacted.

[Source]

The overthrow of China’s proletarian dictatorship meant that China became capitalist. Deng and his allies continued their transitions into state capitalism, and then their successors went far enough to develop more private capitalism. In addition, China became imperialist as it was able to export capital to poorer countries, particularly in Africa and southeast Asia. Is China an Imperialist Country? explains in Chapter 24:

As the economic transformation of China from socialism back to capitalism was completed, China began to show some early signs of its rising new imperialist nature. It began to export capital, and then greatly expanded this, finding special opportunities in the “vacuum” in Africa (which the established imperialist countries had been largely ignoring) and in Latin America and even Europe, in part because of the international financial crisis, thus taking advantage of the weaknesses of the other imperialist powers. And China began working feverishly to expand its military might for the eventual purpose of protecting and expanding its ever-growing foreign economic assets.

[Source]

China’s capitalist restoration was not good for the people, either. The Great Reversal, a book about China’s capitalist restoration and its consequences, shows this in “Introduction: China’s Rural Reforms”:

… [D]own in the southeast corner of Shanxi province five years of heavy capital investment and hard work on the part of the peasants of Long Bow village also came to naught. In 1978, Long Bow villagers had begun the mechanization of almost 200 acres of corn with a collection of scrounged, tinkered, and homemade equipment that did everything from spreading manure to tilling land, planting seed, killing weeds, picking ears, drying kernels, and augering the kernels into storage. The twelve members of the machinery team multiplied labor productivity by a factor of fifteen while cutting the cost of raising grain almost in half. But when the reform, offering subsistence plots to all and contract parcels to the land hungry, broke the fields into myriad small pieces, comprehensive mechanization gave way perforce to intermittent plowing and planting. This left the peasants no alternative but to abandon most of their advanced equipment and reactivate their hoes. When the bank asked for its loan money back the village head said “take the machinery.” But the bank never found a buyer, so to this day the manure spreaders, the smoothing harrows, the sprayers, the sprinkle irrigation sets, the corn pickers, and the grain dryers lie rusting in the machinery yard, mute testimony to a bygone—or is it a bypassed?—era. …

Where once, under a seamless web of adobe villages and their linking roads, clear squares and oblongs of land—green, yellow, and brown—had stretched unbroken to the horizon, now 1,000 kilometers of miniscule strips crowding first in one direction, then in another, in haphazard, never duplicated patterns. This was not “postage stamp” land such as used to exist before land reform, but ”ribbon land,” “spaghetti land,” “noodle land”—strips so narrow that often not even the right wheel of a cart could travel down one man’s land without the left wheel pressing down on the land of another.

After decades of revolutionary struggle, after China’s peasants had finally managed to create a scale and an institutional form for agriculture that held out some promise for the future, some promise that the tillers could at last lay down their hoes and enter the modern world more-or-less in step with their hi-tech-oriented, machine-savvy urban fellow citizens—it had come to this! With one blip on the screen of time, scale and institution both dissolved. The latest page in the great book of history barely rustled as it turned hundreds of millions back to square one.

A stunned peasant comrade said to me, “With this reform the Communist Party has shrugged off the burden of the peasantry. From now on, fuck your mother, if you get left behind blame yourself.”Nevertheless, to me, the irrational fragmentation alone meant the eventual neutralization of whatever advantages the government saw in it or had served up with it to make it palatable. “Noodle land” could only lead, in the long run, to a dead end. I could not think of any place in the world where rural smallholders were faring well, certainly not smallholders with only a fraction of a hectare to their names and that in scattered fragments. The low output of peasants farming with hoes meant that on the average each full-time laborer could produce about a ton of grain a year, one eight-hundredth of the amount I harvested farming with tractors in Pennsylvania. And that ton of grain, worth about $100, would determine the standard of living for countless tillers of the land far into the future. Whatever prosperity any peasant now enjoyed was bound to be ephemeral as the gap between industry and agriculture, city and country, mental and manual labor expanded and the relentless price scissors imposed by the free market opened wide.

[Source]

In a session at the end of his speech about his book (The Unknown Cultural Revolution), Dongping Han talked about his experience in post-socialist China:

The land was privatized in China in 1983. Many people tend to think that farmers are stupid and ignorant. But I think the farmers are very intelligent people. Many of them realized the implications of private farming right away. That was why they resisted it very hard in the beginning. And in my village and in other villages I surveyed, the overwhelming majority of people, 90 percent, said the Communist Party no longer cares about poor people. Right away they felt this way. The Communist Party, the cadres, no longer cared about poor people in the countryside. The government investment in rural areas in the countryside dropped from 15 percent in the national budget in 1970s to only 3-4 percent in the ’80s. So the Chinese public realized that the Chinese government no longer cared about them by disbanding the communes. But I was in college at the time and I didn’t start to think about the issue very hard until 1986. …

Another important change in the rural life was that there were almost no crimes during the Cultural Revolution years. For 10 years, we did not have any crime in the village. In my commune of 50,000 people, I did not hear of any serious crime for 10 years. But now, crime has become so common in China.

[Source]

We must not be pessimistic. Though Chinese socialism was overthrown, it worked well before, and as the contradictions of capitalist-imperialism intensify, we can expect a new proletarian revolution in China as well as in all capitalist countries worldwide! Respect the contributions of Chinese comrades of the past, and support their current fights in modern China!